Today’s topic is about one of the most dreaded things a write can encounter: professional feedback, otherwise known as coverage. How to use and deal with feedback is one of the most important skills for a writer. As a screenwriter, that goes double.

WHAT IS COVERAGE?

Coverage is obtained when a writer submits his or her screenplay to an industry professional for written feedback. The professional does not undertake to produce the script, but instead provides a written report listing its strengths and weaknesses.

The difference between professional coverage and feedback from other people, such as the writers in your writers’ group (you do have a writer’s group, right?) is that you pay for the former. But the principles about how to deal with feedback are the same whether you pay or not.

HOW TO GET COVERAGE

There are many ways to get coverage. Websites and screenwriting gurus abound offering consultancy services ranging from around $50 upwards. The sky is the limit. I have seen consultants ask for thousands of dollars. The pros and cons of these services may depend on where you are as a writer, and I won’t go into whether they are worth the fee here.

You can also approach your peers – other writers. I would not suggest using friends and family unless they are also writers. Your mother will always say your latest torture horror opus is “lovely, dear”. Likewise, friends may not wish to offend you. Those who are not writers may simply lack the skills needed to analyse a script or to tell you whether it is marketable or not. So always go with someone with experience of writing, editing or script reading.

Now let’s dig a little deeper into what coverage means to a writer:

Signs that it’s time to move on.

STANDARD COVERAGE FORMAT FOR SCREENPLAYS

In the film industry, coverage consists of 2-3 pages of synopsis, followed by (usually) 2-3 pages of actual analysis, sometimes followed by a score card. The “meat” of coverage is the 2-3 page analysis. The score card illustrates at a glance the strengths and weaknesses of your work according to that script reader.

What is the purpose of the synopsis, you ask? I submitted my script to get an analysis, not to have my own story told back to me! I’ve been swindled!

Well, it’s tempting to consider the fist 2-3 pages as filler and ignore it. But another way to look at it is to consider that your story may not have translated itself into someone else’s head the way you imagined it in your own.

Writing is the art and craft of transferring thoughts from your own head into someone else’s. It is a kind of telepathy. Whether the other person “gets” your scene or not, or has a different impression of what just happened in your story, can be a sign that you were not successful in getting them to imagine everything as you did.

HOW TO DEAL WITH COVERAGE

Whenever a writer receives feedback, whether verbal or written, the initial reaction may well be to clench your teeth, dig your nails into the arms of your chair, then launch into a tirade about “idiots not getting it” or accusing the reader of skipping important parts that explained everything.

But remember, as a writer your job is to communicate. Just as the customer is king in the restaurant industry, in the writing world the reader is king. If the reader doesn’t get what you want them to get, you have only yourself to blame.

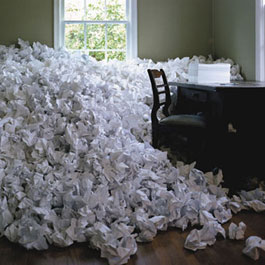

Another reaction is panic. Panic at the amount of work that needs doing. Despair at the insurmountable cliff one faces. Did you spend enough time on your script to begin with? Most writers write around ten drafts of a script and at least two drafts of a novel before even showing it to anyone. Now another rewrite looms. How will you ever get the work done?

Trust me, it’s something everyone dreads.

The way I deal with this is as follows:

Read the feedback all the way through, from start to finish.

Do nothing.

Let it percolate. Don’t be temped to dash off a hasty e-mail cursing the reader for his or her stupidity. If you’re in a writer’s group or face-to-face situation, take the comments with good grace and make a note of them. You will be glad you did. Giving feedback is an art in itself (that’s for another time). Some people are better at it than others. The other person may only wish to help as much as possible. They may think that by being ultra-critical they are only strengthening the material.

Let the dust settle.

After about a week of nursing your feelings by overindulging on cappuccino or another beverage of your choice go back to the feedback. Read it again.

Now that your feelings are out of the way, doesn’t it make more sense? You may even be inspired as you read and gain ideas about how to improve the script. How did you miss that plot point? And of course that character wouldn’t do that!

Maybe the reader knows something after all.

Read it again.

This time, break it down into the things that don’t work. Also make a note of the things the reader liked. Don’t change these. These are your story’s strengths.

I always copy the feedback into another document, then edit it down so that I just have the reader’s criticisms bullet-pointed in a list.

Still looks like an awful lot of wok, doesn’t it?

Here’s a secret tip.

Do the easy stuff first!

Did you use the wrong word somewhere? Commit a typo? Attribute dialogue to the wrong character. Go and change that sucker now. Each time you do, remove that point from your document.

Feels good, right?

You’re making progress!

NOW FOR THE REAL WORK

At this point, go back over your shortened document. Now separate the points out into things like “STORY”, “CHARACTER”, and “DIALOGUE”.

I now go through the script one time for each of these things. Take another pass for story problems, then another for character and dialogue etc. I recommend Paul Chitlik’s excellent book “Rewrite” for a structured approach. If you already did this, now’s the time to do it again.

By taking a structured, methodical approach to addressing feedback, you can make the process of rewriting much less painful.

If you find yourself unwilling to throw out a cherished scene or piece of dialogue, simply save another version of your novel or screenplay file. You can always go back to it. And you may find that without the psychological crutch of having it there you’ll find a much better way to write that scene or show that character’s journey.

Feedback is painful. It’s painful because we writers like to believe that what’s on the page is a little bit of our soul. And rejection hurts. But that’s not how it is. Rare is the script that cannot be improved, even Oscar-winning screenplays. Henry James, the great American novelist, used to return to his stories and tinker with them ad infinitum.

By taking time to let your wounded pride recover, you can approach feedback with a clear head. By breaking it down into small tasks, you can make rewriting seem less daunting. If you do these things, receiving feedback may become less like a chore.

As always, if you think I’ve missed anything, or disagree with me, let me know. I welcome the feedback!

Happy (re)writing!

POSTSCRIPT:

There will come a time when you cannot rewrite any more. Recognising this is just as important as knowing the script needs improvement. When you reach this stage, don’t delay. Get it out there! Form a marketing plan and execute it. Don’t let someone else beat you to the punch. This has happened to me several times. There’s nothing worse than seeing someone sell your idea to a studio when your script is sitting on a shelf waiting to be marketed!